It has become known as the first genocide of the 20th century: tens of thousands of men, women and children shot, starved, and tortured to death by German troops as they put down rebellious tribes in what is now Namibia. For more than a century the atrocities have been largely forgotten in Europe, and often in much of Africa too.

Now a series of events – and a policy U-turn by Berlin – is raising the international profile of the massacre of Herero and Namaqua peoples and bringing justice for their descendants a little closer. Negotiations between the German and Namibian governments over possible reparation payments are expected to be completed and result in an official apology before next June.

In Berlin a major new exhibition about the country’s bloody colonial history opened earlier this winter. It features letters from missionaries expressing their concerns about concentration camps and killings in Germany’s south-west African colony.

In the US activists have hired lawyers to pressure the United Nations. Elsewhere there are plays exploring the tragic story and displays of photography at high-profile contemporary art fairs.

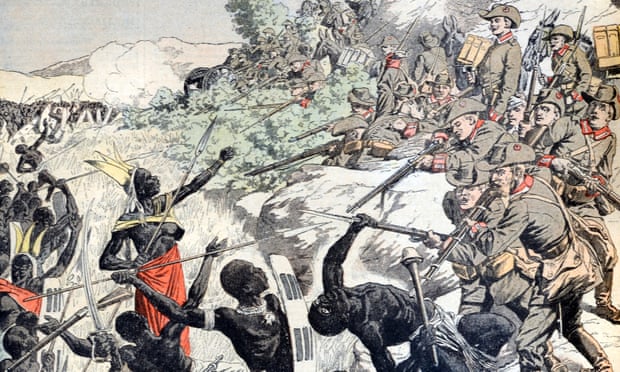

In 1884, as European powers scrambled to carve up Africa, Berlin moved to annex a new colony on the south-west coast of the continent. Land was confiscated, livestock plundered and native people subjected to racially motivated violence, rape and murder. In January 1904, the Herero people – also called the Ovaherero – rebelled. More than a hundred German civilians were killed. The smaller Nama tribe joined the uprising the following year.

Colonial rulers responded without mercy. Tens of thousands of Herero were forced into the Kalahari desert, their wells poisoned and food supplies cut. Gen Lothar von Trotha, sent to quell the revolt, ordered his men to shoot “any Herero, with or without a rifle, with or without cattle”.

“I do not accept women or children either: drive them back to their people or shoot them,” he told his troops. The order was rescinded but other measures were employed that were equally lethal.

Those who had survived were rounded up and placed in concentration camps, where they were beaten and worked to death in squalid conditions. Half of the total Nama population were also killed, dying in disease-ridden death camps such the infamous site on Shark Island, in the coastal town of Lüderitz. By 1908, only 16,000 remained, historians say.

As many as 3,000 Herero skulls were sent to Berlin for German scientists to examine for signs that they were of racially inferior peoples.

“We are talking now about the lives that were lost, the land that was taken, the cattle that was killed, the rape, the lost dignity, the culture that was destroyed. We cannot even speak our language,” said Esther Muinjangue, a Herero activist and social worker at the University of Namibia, in Windhoek, the capital.

Thousands of women were systematically raped, often taken as “wives” by settlers. “My great-great-grandfather was German. This relationship was not of love, but a product of force,” Muinjangue added.

Ongoing struggle

The issue has long caused tensions in Namibia, where farmers descended from the original German settlers still own land seized from local people. The Herero, who make up about 10% of Namibia’s population of 2.3 million, say they never regained a fraction of their former prosperity.

“We live in overcrowded, overgrazed and overpopulated reserves – modern-day concentration camps – while our fertile grazing areas are occupied by the descendants of the perpetrators of the genocide against our ancestors. If Germany pays reparation then the Ovaherero can buy back the land that was illegally confiscated from us through the force of arms,” said Veraa Katuuo, a US-based activist.

Resentment has been rising for years. Earlier this year red paint was poured over a German colonial monument in the town of Swakopmund.

Germany was forced out of the colony in 1915, but the killings there and in its territories on the east coast of the continent are seen by some historians as important steps towards the Holocaust in Europe during the second world war.

In Germany, debate around the country’s colonial project has long been overshadowed by the crimes of the National Socialist era. While most German cities commemorate the victims of the Nazi period, there are no significant monuments to the victims of German colonialism.

Other than a memorial stone in a cemetery in Berlin’s Neukölln district and a statue of an elephant in Bremen, no permanent display currently bears testament to the genocide of the Herero.

German officials rejected the use of the word “genocide” to describe the killings of the Herero and Namaqua until July 2015, when the Social Democrat foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, issued a “political guideline” indicating that the massacre should be referred to as “a war crime and a genocide”.

But there are still strict limits. German chief negotiator Ruprecht Polenz told The Guardian that personal reparations to relatives of Herero and Namaqua victims were “out of the question”. His position has angered senior Herero and Nama leaders, and a meeting in Windhoek in November ended with representatives of the Nama genocide committee storming out of the German embassy after Polenz said that massacre in south-west Africa was “incomparable” to the Holocaust.

“We understand that the German government is proposing an apology without reparations. If that is the case, it would constitute a phenomenal insult to the intelligence not only of Namibians and the descendants of the victim communities, but Africans in general, and in fact to humanity … It would represent the most insensitive political statement ever to have been made by an aggressor nation to the victims of its genocide,” said Vekuii Rukoro, the paramount chief of the Herero.

Instead of direct payments, German negotiators have proposed setting up a foundation for youth exchanges with Namibia and funding various infrastructure projects, such as vocational training centres, housing developments and solar power stations. But this means bilateral discussions between the Namibian government and Berlin, without Herero or Namaqua participation. Herero representatives say they are being marginalised.

“Development aid never goes to the Herero or Namaqua areas,” said Festus Muundjua, secretary for foreign affairs of the Ovaherero Traditional Authority.

Another key issue is the return of human remains stolen by the Germans. Twenty skulls were returned in 2011 to be welcomed by warriors on horseback, ululations and tears. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, remained.

‘Uncomfortable thesis’

Jürgen Zimmerer, a historian at Hamburg University and consultant to the new exhibition, argued that “colonial amnesia” had created a warped perspective on later German crimes in the 20th century.

“If you focus only on the 30 years of imperial Germany’s excursions into Africa, then of course the story pales in comparison to the colonial histories of other European nations, such as Britain or Belgium,” Zimmerer said.

“But it’s important to see Germany’s history in Africa as continuous with its better-known dark chapters in the 30s and 40s. In Africa, Germany experimented with the criminal methods it later applied during the Third Reich, for example through … the colonisation of eastern and central Europe … There is a trend among the public to view the Nazi period as an aberration of an otherwise enlightened history. But engaging with our colonial history confronts us with a more uncomfortable thesis.”

Recent historical works have highlighted the links between the fate of the Herero and Nama, and that of European Jews. Ideas and techniques that would play a key role in the Holocaust have some of their roots in German atrocities in colonial Africa, researchers argue.

Other former colonial powers have been deeply reluctant to acknowledge the violence associated with their imperial history. Belgium has never officially recognised the cost of its invasion and exploitation of Congo, where about 10 million people – roughly half the country’s population – are thought to have died during its rule.

In 2013 the UK government reluctantly offered “sincere regret” and £2,600 each to about 5,000 Kenyans imprisoned and tortured during the Mau Mau rebellion in the former colony in the 1950s.

A video of Indian politician Shashi Tharoor demanding a token £1 reparation to India from the UK at the Oxford Union attracted more than 3m views on YouTube last year, and earned an endorsement from Narendra Modi, the Indian prime minister.

“Reparations payments to Namibia could set a precedent for Belgium and the Congo, France and Algeria or Great Britain and the history of the slave trade. Descendants of the Herero know that too,” Zimmerer, the historian, said. Some experts have argued reparations would be impractical.

Rukoro, the Herero chief, rejected what he called Germany’s “chequebook diplomacy” and bilateral dealings with the Namibian government. “Guess what: the Hereros and the Namas of Namibia will never … declare ceasefire with generations of German governments to come. Our war will continue,” he said.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

News: Germany moves to atone for 'forgotten genocide' in Namibiahttps://goo.gl/PsCt0y

0 comments:

Post a Comment